![]()

“This is the hardest thing I’ve done in my life.”

I laughed at the pale, sweating, panting creature who uttered that sentence. He was struggling up the slick granite of Half Dome, clinging to the cables for dear life. I was sailing down the same cable route. I was lean, brown, and strong. I’d spent the summer in the Sierra sun, sometimes covered in nothing more than a thin layer of DEET oil. I slept at 8000 feet and hiked miles a day at higher altitudes for the National Biological Service. I spent my weekends bagging peaks. The hike to Half Dome’s base had been long, but not overly strenuous. The cable route up its steep backside was fun: a diversion from the boring, dusty miles between the Merced river and the ropes. My friends and I had raced up the dome, lazily surveyed the top, and made a game of sliding back down. I was twenty years old and on top of the world.

After spending a glorious summer living and working in Yosemite, I never returned. I bounced around from Washington to Alaska to Arizona to Virginia to North Carolina to Japan to Ohio before I realized how special my Yosemite experience had been. When I planned my 40 adventures for my 39th year, hiking Half Dome was the fourth one I listed. It represents the freedom and power I felt during my Yosemite summer. Returning, 19 years later to repeat the hike, required that I reclaim both.

In the years between my summer in Yosemite and my return to California, the park put a quota on the number of hikers permitted up Half Dome’s cables each day. A maximum of 300 persons are allowed up each day to protect wilderness character, reduce crowding, protect natural and cultural resources, and improve safety.The permits to hike are issued in a preseason lottery with an application period of March 1 to March 31. However, in 2015, I missed the lottery.

Thankfully, a daily lottery is held during the hiking season with up to 50 permits up for grabs each day. Potential hikers apply two days before their hoped-for date and are notified late on the day of the application. The competition for spots is less fierce on weekdays, so, in early September, I identified a number of dates in September and October and planned to apply repeatedly until I was successful.

I have no luck in games of chance. I am never a Bingo winner. I don’t even bother with Powerball or Scratch-Offs. I’ve never won a raffle. But I won the very first Half Dome permit for which I applied!

It takes 10-14 hours to complete the hike. Depending on the route, the trek is 14.2 or 16.5 miles, but a 4800 foot elevation gain either way.

![]()

The first 1.5 miles of the trail are paved, but steep. Here, the trail looks deceptively like a sidewalk, but the grade is no “walk in the park.” To make the shorter, 14.2 mile hike, I took the left fork and followed the Mist Trail up hundreds of stone stairs past Vernal Falls and then Nevada Falls. Finally, after the exhilarating, 2,000 foot climb, above both falls, I was at the Merced River and the final junction with the John Muir trail.

The Merced is the halfway point between Happy Isles and Half Dome and the last reliable source of water. I pulled out my filtration system and topped off my bottles. I was as prepared as possible for the next dusty, dry four miles to the cables.

![]()

The march to the base of the dome from the river is incredibly boring, enlivened only by glimpses of the destination. After an uneventful, flat trek along the river, the route begins endless switchbacks up the forested hump that butts up against the backside of the granite dome. I entertained myself by passing and being passed by the other hikers and sniffing the Jeffrey Pine. (Stick your nose in the crevices of a Jeffrey Pine’s bark and inhale. The sap smells like butterscotch or vanilla.)

I finally reached the permit checkpoint a little before noon. I presented my permit to the ranger and walked onto the dome.

The first portion of the granite walk is not the cables, but terrifying, nonetheless. Stone stairs switchback up the first hump. There are no guardrails. The steps are narrow, uneven, and often covered in a fine layer of coarse sand. A misstep here can send the clumsy hiker down a steep, sometimes sheer, rock slope. I’m just such a clumsy hiker and slipped a few times, but recovered before falling from the trail. Finally, the path just disappears, but I knew to follow the naked rock up to its zenith. From there, I could see down the false summit to a depression and the start of the cable route.

As I stared at the ant-like figures hauling themselves up the cables, a hiker passed me, on his way off the dome. He was removing leather gloves and I suddenly realized that dragging my hands up the steel cables for 400 vertical feet would leave my palms absolutely raw. The hiker saw my panic and assured me that there was a pile of gloves ahead.

![]()

I reached the base of the cables and, indeed, found a pile of gloves in a rock cranny. Always the fashionista, I chose a turquoise pair of gardening gloves with a mod flower pattern in hot pink and chartreuse. The palms were coated in a grippy, clear rubber. I pulled the first one on and discovered it was damp with the previous wearer’s sweat. I decided this was a lucky sign and donned its mate. I stepped into the cable route with preperspired hands.

![]()

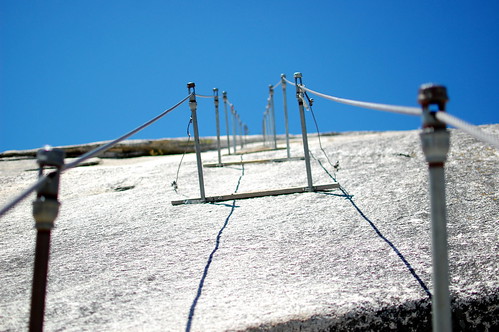

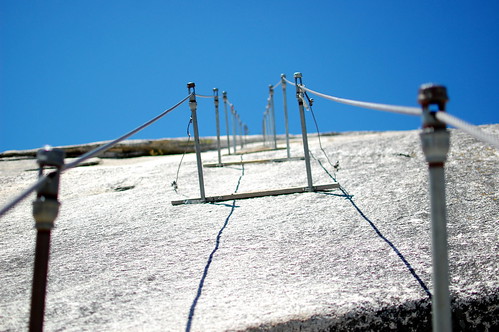

The cables are steel and run from anchors in the rocks, through the tops of poles set roughly every ten feet up the slope. The cables function as both handrails and climbing aids. The rock surface is glacier-polished granite, shiny-slick in most places, but cracked and rough in a few others. Wooden planks are anchored at every set or every other set of poles. These offer a place to rest and catch one’s breath or simply allow another hiker to safely pass. The rock itself is usually too slick and steep to comfortably pause.

The excitement of finally reaching the cables spurred me to an energetic start. No hikers were ascending close ahead of me (but some were descending), so I had little impediment to my quick pace. I fully trusted my gear (to include the borrowed gloves), my abilities, and the cables themselves. I was halfway up the rock before my arms began to shake.

I had been hauling myself up, with a hand on a cable to each side, with tremendous effort. I was in a rocking side-to-side rhythm, smoothly transitioning to a hand over hand on a single cable when passing another hiker. As I gained altitude, I was grateful for the muscles built by swimming and T25 . . . until my adrenaline burst petered out and I realized that if my arms gave out on me, I’d be dead.

![]()

I paused on the next wooden plank, terrified and shaking, and wondered, “Is this the hardest thing I’ve ever done?” Certainly not. “Am I a fool for hiking this alone?” Perhaps. “Will I be able to continue?” Yes. And I did. The shaking steadied. My arms did not fail. And, thankfully, no smug 20-year-old passed me during my moment of panic.

I made steady, but steadily slower, progress up the cables. Although I no longer had fears about my arms collapsing, my breaths were ragged. For the last 25 yards, I paced myself by pausing at each plank for 5 breaths before continuing on. At last, I crested Half Dome.

![]()

Like the hikers before me, and those I saw summit after me, I spent the next fifteen minutes roaming the top of Half Dome in a daze. The top is remarkably featureless. The views are remarkably astounding. Framed by nothing but man-made cairns, the 360-degree vista is unreal. The blue sky, gray stone, and green trees visible in every direction have the soft quality of a watercolor. The occasional chatter of a hiking group and the tug of a breeze is the only reminder that the experience is real, not a painting or a dream.

Most hikers congregate along the visor, the lip of stone hanging over Half Dome’s severe northwest face, towering over Yosemite Valley. I ate my sandwich gazing into the valley’s blue depths. I chewed as I contemplated hikers dangling their legs over the edge while their friends snapped pictures. I contented myself with a selfie a safe-ish distance from the edge. For an extra thrill, I belly crawled to a sheer drop and looked down. As terrifying as the cable route may be, the thought of climbing the sheer face puts that experience to shame.

![]()

Before descending, I waited for a small group to finish the cable ascent, cheering them on with my own experience still fresh in my memory. Then, I began sliding down with abandon.

![]()

I imagine that I descended with the same sense of joy that I had when I was twenty. Facing uphill, letting my sassy gloves take the friction, I almost ran backwards down the hill. My hands began to heat through the layers of plastic and fabric. I made a game of seeing just how fast I could go, stopping only to let others ascend and speak words of encouragement. As another hiker passed me, he bumped against my camera and my lens cap went pinwheeling down the steep curve. It was lost to the dome and so was I as I resumed my downhill sprint. I paused at a plank to allow an uphill hiker pass and he said, “This is the hardest thing I’ve ever done.” I didn’t laugh. I just nodded in understanding and told him that the view was totally worth it.