Morning Snack

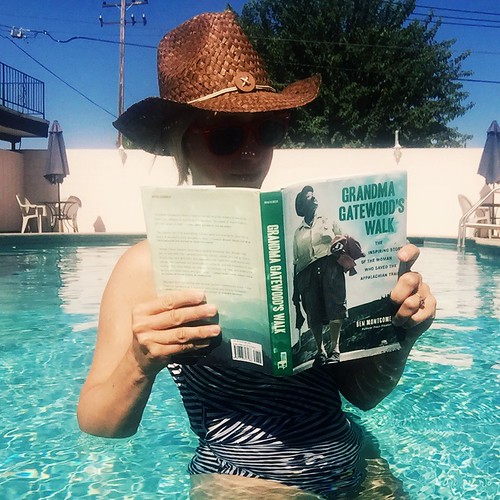

I start the day with coffee and a Larabar while I write my Morning Pages. I won’t eat breakfast until I’ve written in my journal and completed my workout.

Breakfast

Breakfast was my High Protein Crunchy Granola for the first part of the summer, but I’m now eating 2 or 3 eggs and a corresponding number of corn tortillas fried in coconut oil and salted. Sometimes I add green onions or avocados.

Lunch

Lunch is four roll-ups prepared as follows:

Wrap: corn tortilla fried in coconut oil and salted

Sticky stuff: hummus or peanut butter* (when I run out of ice to keep the hummus cool)

Veggies: sprouts, sun-dried tomatoes, and/or green onions

Main event: baked tofu, avocado, and/or smoked salmon

Hiking Snack

I pack trail mix and fresh or dried fruit into my pack to eat before, during, or after lunch.

Afternoon Snack

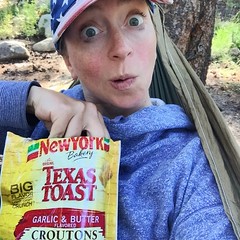

I crave salty, crunchy snacks after a hike. On my least healthy days, that means french-fried onions or croutons. (I know these foods are terrible for me. It’s an addiction.) When I have more nutritionally sound options, I eat Terra chips (Sweets & Beets** are my favorite) or I make blistered shishito peppers (well salted, of course).

Dinner

I follow this formula for dinners: protein + carb + veggies (if I have any). This is usually expressed as one of the following meals:

Tofurky sausage + gnocchi

Chickpeas + whole wheat pasta

Textured vegetable protein (with taco seasoning) + fried corn tortillas (= TVP tacos!)

I dress the first two options in lemon juice, olive oil, and salt or pesto sauce.

Even with the extra protein, most of my calories come from fat and carbs because these things don’t usually require refrigeration. I wish it were possible to eat more produce, but it spoils so quickly, cooler space is limited, and preparation is difficult without a real kitchen. I eat almost no added sugar. I eliminated most sugar from my diet last spring because of issues with hormonal acne. My diet is also fairly low in wheat (except for those croutons!) I’m making the best of things and trying to make healthy choices.

What do you eat while on a long camping/hiking trip?

It took me less than 11 weeks to consume this entire container.

*Peanut butter and tofu roll-ups are good. I pretend they're Thai-inspired. I haven’t tried peanut butter and avocado, but I’m game. I don’t think I could bring myself to eat peanut butter and smoked salmon.

**WHY can I only find these unsalted? It’s an easy fix with my salt shaker, but creating salt-less chips is just sadistic.